Disclaimer: This article provides general information about USCIS translation requirements and professional best practices. It does not constitute legal advice. If your case involves complex legal issues, consult a qualified immigration attorney.

About the author: Erin Chen is the Co-Founder and Translation Strategist at CertOf™. With over a decade in bilingual editorial risk control and hands-on experience navigating the U.S. immigration process, Erin helps applicants prepare USCIS-ready certified translations that reduce avoidable delays.

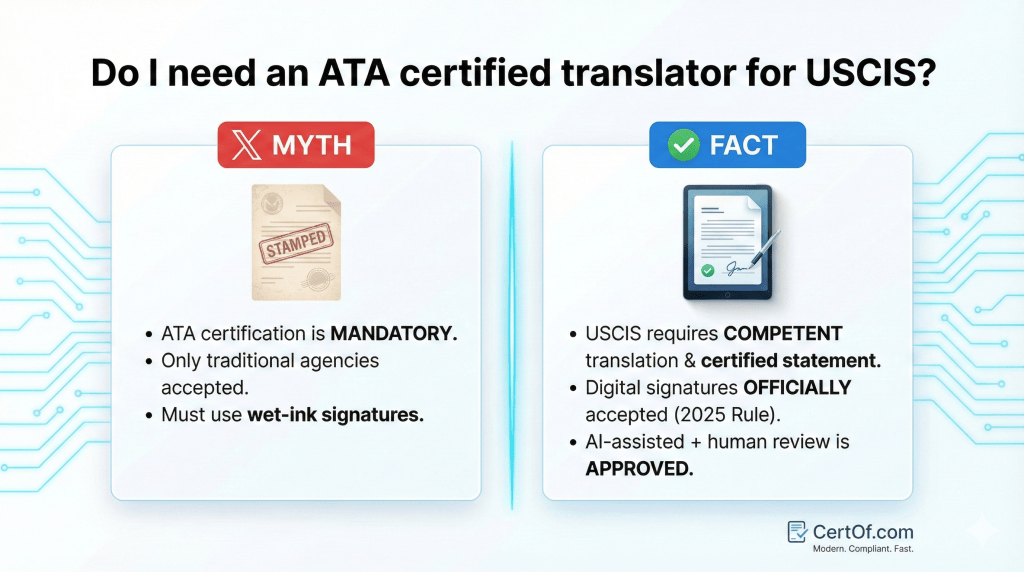

Quick Answer: No ATA Requirement, But “Competence” Really Matters

If you are preparing an I-130, I-485, N-400, or another USCIS filing in 2025, you have probably seen this warning on forums or from well-meaning friends:

“You must use an ATA certified translator for USCIS or your case could be rejected.”

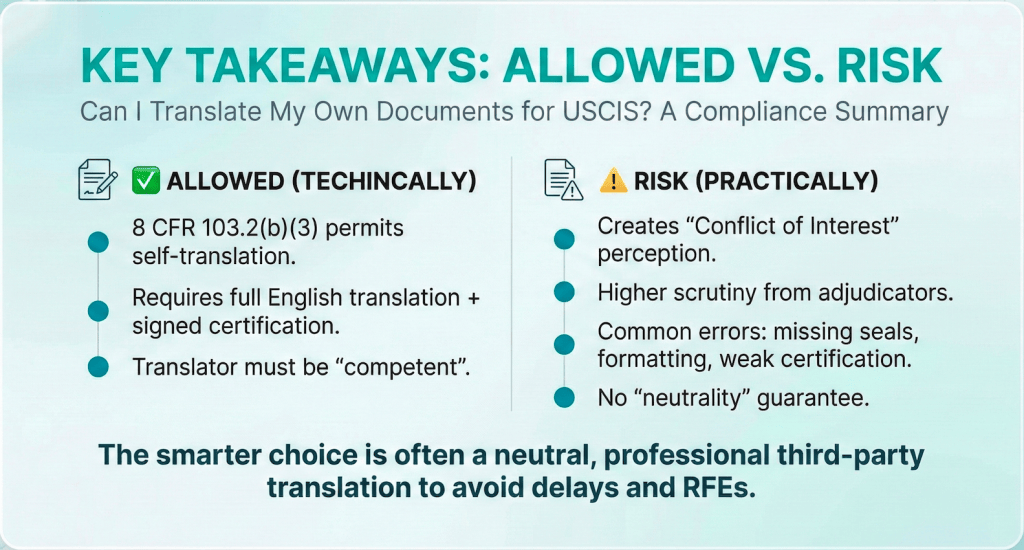

That sounds serious, but it is not what the regulation actually says. USCIS applies 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3), which requires a full English translation plus a signed statement that the translator has provided a complete and accurate translation and is competent to translate from the foreign language into English. The rule does not mention the American Translators Association (ATA) or any specific professional credential.

The real question for 2025 is not “Do I need an ATA translator?” but rather “How do I make sure my certified translation is technically correct, low-risk for RFEs, and reasonably priced?”

Key Takeaways for 2025 USCIS Applicants

- USCIS does not require an ATA certified translator. The legal standard is a complete, accurate translation plus a signed statement of competence under 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3).

- For most filings, USCIS accepts scanned or photocopied signatures on the translator’s certification, as long as there is an original “wet ink” signature behind that copy. You usually do not need a physical original mailed to you just for USCIS.

- USCIS rules focus on accuracy and accountability, not on which tools the translator used. AI-assisted translations can be acceptable if a competent human reviews the text and signs the certification.

- The most common translation-related RFEs are caused by non-literal wording, incomplete translations, and missing or sloppy certification language—not by a lack of ATA membership.

- ATA-certified translators still make sense in a narrow set of high-stakes or highly technical cases, but are often overkill for routine civil documents.

Do I need an ATA certified translator for USCIS?

1. What 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3) Actually Says About Translations

The core USCIS rule for foreign-language documents is contained in 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3). In plain language, it says that any foreign-language document submitted to USCIS must be accompanied by:

- a full English translation, and

- a certification in which the translator states that the translation is complete and accurate and that they are competent to translate from the foreign language into English.

There is no mention of ATA, of specific licenses, or of government-issued “translator cards.” The regulation focuses on the content and completeness of the translation and on the translator’s willingness to sign their name under that statement.

If you want to see what a compliant package looks like, you can review a full sample in our USCIS certified translation sample article. It shows how the original document, translation, and translator’s declaration come together in a single PDF.

2. Why the “ATA Certified Translator” Myth Is So Persistent

So if the law does not require an ATA certified translator, why is this myth so common?

There are three main reasons:

- Risk-averse habits. Some lawyers and agencies prefer to over-specify requirements (“only ATA members”) because it sounds safer, even when the regulation is broader.

- Marketing language. Many translation providers use phrases like “ATA certified translators” in advertising. Over time, applicants start to confuse marketing language with legal requirements.

- Misunderstanding the term “certified translation.” In the U.S. context, a “certified translation” usually means a translation accompanied by a signed statement from the translator, not a government-issued seal or license.

None of this means ATA certification is bad. ATA maintains rigorous exams and can be a strong quality signal, especially for complex legal or technical work. But for a typical USCIS application, what the officer is really looking for is a correctly formatted certificate of accuracy that clearly identifies a responsible human translator.

3. 2025 Reality: Scans, Reproduced Signatures, and Digital Workflows

Another source of confusion is whether USCIS will accept translations that are delivered electronically and printed or uploaded as scans, or whether everything must bear “original ink.”

USCIS guidance now makes clear that, for most paper-filed benefit requests, they will accept a reproduced original signature—for example, a scanned, faxed, or photocopied version of a document that was originally signed in ink. That principle applies both to application forms and to supporting documents, including translators’ certifications, as long as an original wet-signed version exists and is retained in case USCIS asks to see it later.

In practice, this means your translator can sign the certification, scan it, and deliver the whole certified translation as a PDF. You can then print or upload that PDF with your USCIS filing without waiting for physical mail, unless your attorney or a specific agency explicitly demands originals.

It is important to distinguish this from full electronic signature platforms. For most paper-filed USCIS forms and supporting documents, the standard is still an original handwritten signature that is then reproduced electronically. Pure “click-to-sign” signatures on PDFs may be treated differently from scans of ink signatures, so when in doubt it is safer to use a traditional wet signature that is then scanned.

4. Can I Use AI-Assisted Translation for USCIS Documents?

The regulation does not forbid specific tools. USCIS cares about two things:

- Is the translation complete and accurate?

- Is there a named individual who certifies that accuracy and competence in writing?

Behind the scenes, many modern providers now use AI-assisted translation to speed up the process and handle formatting, especially for multi-page PDFs or complex tables. This is acceptable as long as a competent human thoroughly reviews the result and personally signs the certification.

What is not acceptable is pasting raw machine output—such as an unedited Google Translate result—into a document and signing it without careful review. That is exactly the kind of shortcut that leads to mistranslations, missing sections, and RFEs.

If you are curious about the risks of doing everything yourself with tools like Google Translate, you can read our dedicated guide: Can I Use Google Translate for USCIS?

At CertOf™, we use AI primarily to mirror the layout of your original document and support the human translator, not to replace them. A translator still checks every line and signs a personal statement of accuracy and competence.

5. Real Reasons Translations Trigger RFEs or Delays

From an officer’s perspective, a translation is a piece of evidence. They do not care how fancy the logo is—they care whether they can rely on it quickly. In 2025, the most common translation-related problems tend to fall into a few patterns.

Pitfall 1: “Interpretive” Instead of Literal (Word-for-Word) Translation

Officers expect a literal, word-for-word translation unless the document itself uses highly idiomatic or archaic language. Problems arise when translators simplify or summarize:

- Original: “No criminal record has been found in this jurisdiction to date.”

- Translated: “Clean record.”

The shorter phrase might feel equivalent, but it does not actually reflect each part of the original sentence. That can trigger questions or an RFE asking for a more precise version.

A safe practice is to instruct your provider to use literal, mirror-style translation for USCIS and to avoid “cleaning up” the document beyond necessary clarity.

Pitfall 2: Incomplete Translation of Long Documents

Bank statements, divorce decrees, court judgments, and academic transcripts can span many pages. USCIS expects a full English translation, not just “important pages.” Omitting annexes, footers, or back pages can lead to delays or RFEs, especially in more scrutinized case types.

If you suspect your case might be sensitive, err on the side of translating the full document and make sure page numbering is clearly indicated in both the original and translation.

Pitfall 3: Confusing Formatting

Officers work under time pressure. If they cannot easily match each block of translated text to the corresponding block in the original document, they may treat the translation as low-quality or incomplete.

This is why we use mirror formatting at CertOf™: the layout of the translation (tables, headings, stamps, seals) mirrors the original so that the officer can move back and forth with minimal effort. You can learn more about real-world rejection scenarios in our article USCIS Rejected My Translation: What Went Wrong and What to Fix.

Pitfall 4: Sloppy or Missing Certification Language

Finally, some translations fail because the certification itself is incomplete. Typical problems include:

- No explicit statement that the translation is “complete and accurate.”

- No statement that the translator is “competent to translate from [language] into English.”

- No contact information for the translator or translation provider.

A robust certificate of accuracy should clearly include all of these elements on one page, signed and dated, and ideally attached in the same PDF as the translation itself.

6. When an ATA Certified Translator Might Be Worth the Cost

There are situations where paying for an ATA certified translator is not just marketing—it is a sensible risk-management decision. For example:

- Immigration Court (EOIR) proceedings. If you are in removal proceedings, the stakes are much higher and the judge may look more critically at translations. Your attorney may reasonably insist on ATA credentials or even a specific individual.

- Highly technical or scientific evidence. For O-1, EB-1, or complex employment-based cases involving patents, medical records, or scientific articles, a subject-matter specialist who also holds ATA certification can add real value.

- Foreign consulates with special rules. Some consulates and civil registries outside the U.S. require sworn or court-appointed translators, which is a different system from USCIS certified translation. Our comparison article Certified vs. Notarized Translation explains these distinctions in more detail.

For routine USCIS filings involving birth certificates, marriage certificates, police clearances, and academic records, an ATA membership is usually optional. A focused, USCIS-experienced provider that follows 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3) carefully is often the more efficient choice.

7. How to Choose a Safe USCIS Translation Provider in 2025

Instead of asking only “Is the translator ATA certified?”, consider these practical questions:

- USCIS focus. Does the provider clearly state that they specialize in USCIS certified translation requirements, not just generic “business translation”?

- Turnaround time. Can they deliver within hours, not days, without cutting corners on quality?

- Mirror layout. Do they preserve tables, stamps, and seals so that officers can easily compare documents?

- Clear certification. Is the certificate of accuracy explicit, complete, and signed by a named individual?

- Guarantee. Will they stand behind their work if USCIS raises a translation-related concern?

At CertOf™, we designed our workflow around these checkpoints. You can upload scans of your documents, preview the layout, and receive a USCIS-compliant, mirror-formatted certified translation—typically in 5–10 minutes per document—without paying ATA-level prices for routine cases.

To see how this works in practice, you can start directly from our secure translation page: CertOf™ USCIS Certified Translation.

8. FAQ: ATA Translators and USCIS Translation Requirements

Do I need an ATA certified translator for USCIS?

No. The regulation requires a complete and accurate translation plus a signed statement that the translator is competent. It does not require ATA membership. ATA certification can be useful in complex or high-stakes matters, but it is not a formal USCIS requirement for typical family-based or naturalization cases.

Does USCIS accept online or PDF certified translations?

For most paper-filed applications, USCIS accepts printed or uploaded copies of documents that bear a reproduced original signature. That means your translator can sign the certificate of accuracy, scan it, and deliver the package as a PDF. You then print or upload that PDF with your filing. Keeping the original wet-signed version in your records is a good practice in case it is ever requested.

How long is a certified translation valid for USCIS?

For static documents (such as birth or marriage certificates), a properly certified translation does not “expire” under USCIS rules. However, the underlying document may need to be recent in some contexts (for example, police clearances). For a deeper discussion, see our article How Long Is a Certified Translation Valid for USCIS?.

Can I translate my own documents if I am bilingual?

Technically, 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3) does not explicitly prohibit self-translation, but it is usually a bad idea. Officers may see a conflict of interest, and you may miss small nuances that an experienced certified translation provider would catch. We explain the risks in detail in Can I Translate My Own Documents for USCIS?.

Do I ever need notarized translation instead of “just” certified translation?

USCIS itself rarely requires notarized translations. However, some state courts, consulates, or licensing boards do. Notarization is about verifying the identity of the person signing the certification, not about language quality. Our guide Certified vs. Notarized Translation explains when each is appropriate.