Disclaimer: This article provides general information about USCIS translation requirements and professional best practices. It does not constitute legal advice. If your case involves complex legal issues, consult a qualified immigration attorney.

About the author: Erin Chen is the Co-Founder and Translation Strategist at CertOf™. With over a decade in bilingual editorial risk control and hands-on experience navigating the U.S. immigration process, Erin helps applicants prepare USCIS-ready certified translations that reduce avoidable delays.

If you are holding a birth certificate, marriage record, or police clearance in another language, you are probably asking the same question every applicant asks sooner or later: who can certify a translation for USCIS?

Do you really need a lawyer? Is a notary at the UPS store enough? Can your bilingual friend just “sign something” for free?

As a Translation Strategist who has helped thousands of applicants — and as someone who has gone through the U.S. immigration process myself — I know how much an RFE (Request for Evidence) can disrupt your life. The rule on paper looks simple, but in 2025 the wrong choice about who certifies your translation can easily add months to your timeline.

In this guide, I will clarify who can certify a translation for USCIS under the official rule, why “free” friend translations often become the most expensive option, and how to choose a safer, more predictable path.

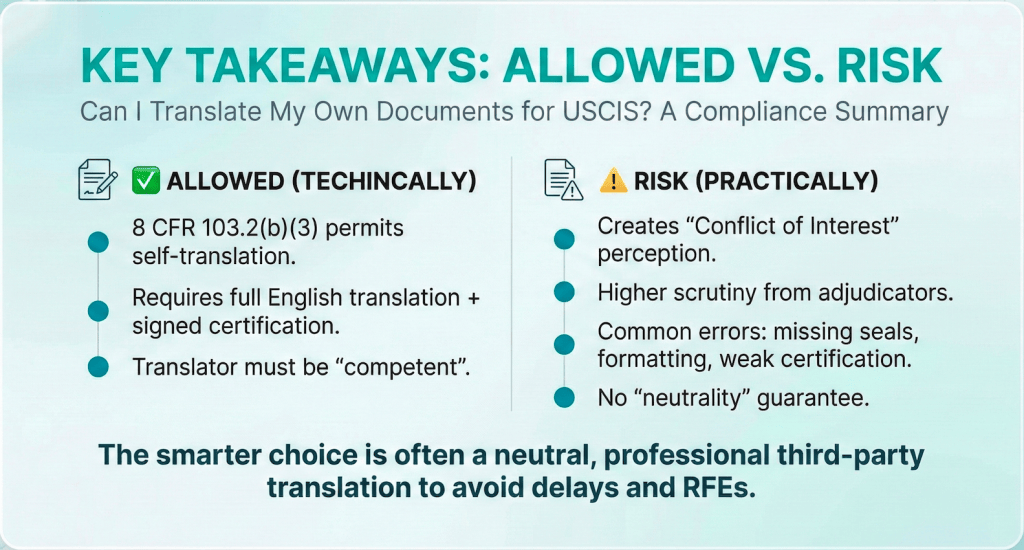

Who Can Certify a Translation? (Key Takeaways for 2025)

- The legal core: USCIS requires a full English translation plus a signed certification that the translation is complete, accurate, and done by someone competent in both languages.

- Self-translation: Not explicitly banned in the regulation, but viewed as a conflict of interest and treated as high risk in practice.

- Friends and relatives: Technically allowed if truly competent, but often scrutinized heavily for bias and small mistakes.

- Notaries: A notary verifies identity and signatures, not translation quality. USCIS usually does not require notarization for translations.

- Professional certified translations: Third-party services that specialize in USCIS tend to be the least risky option for core civil documents.

- 2025 enforcement trend: Officers look closely at whether each document has its own certificate, whether the translation is word-for-word, and whether the signature on the certification is real and traceable.

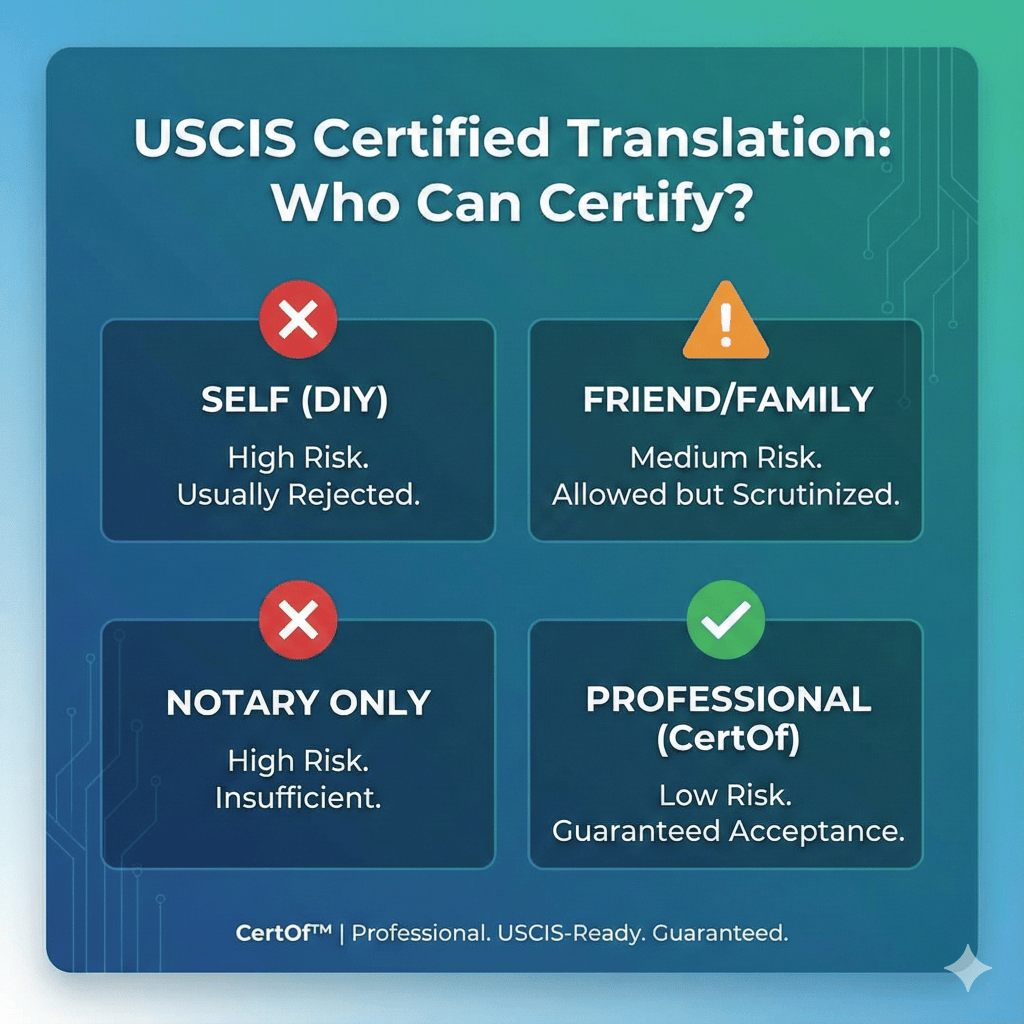

Self vs friend vs notary vs professional options

The Official USCIS Rule on Certified Translations

The governing language is in the Code of Federal Regulations. Under 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3), any document in a foreign language submitted to USCIS must be accompanied by a full English translation that the translator has certified as complete and accurate.

A compliant certification statement must include at least three elements:

- A statement that the translation is complete and accurate.

- A statement that the translator is competent to translate from the foreign language into English.

- The translator’s signature, printed name, and date.

Notice what the rule does not require. It does not say the translator must be a lawyer, a court interpreter, or a notary public. The emphasis is on competence and on the translator’s declaration of accuracy, not on a specific job title.

For a deeper breakdown of the exact wording and examples of certification statements, see our detailed guide on USCIS certified translation requirements.

2025: Same Rule, Tougher Enforcement

From 2023 to 2025, the text of 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3) has not been rewritten. What has changed is how strictly officers apply it in the middle of large backlogs. In real cases, three themes keep coming up:

- One certificate per document: “Blanket certificates” that try to cover several unrelated translations with one generic statement are much more likely to be questioned. Best practice is a separate certificate of translation accuracy for each document (birth certificate, marriage certificate, police record, etc.).

- Literal, word-for-word translations: Officers expect seals, stamps, headings, and back-side content to be translated, not just the main body text. Partial or summarized translations are a common RFE trigger.

- Real signatures, including scanned: USCIS generally accepts high-quality scans of original handwritten signatures on many filings, and the same logic applies to translator certifications attached to those filings. A purely typed name with no real signature is easier to challenge.

The Four Real-World Options: From Riskiest to Safest

1. Can I Certify My Own Translation for USCIS?

This is the classic DIY instinct: you are fluent in English and your native language, you understand your own documents better than anyone else, and you want to save money.

Legally: the regulation does not explicitly say “you cannot translate your own documents.”

Practically: self-translation is one of the fastest ways to make your case look fragile. You are both the beneficiary and the translator. If there is any inconsistency, the officer has to ask whether the translation was quietly edited to make your case stronger.

From an officer’s perspective, this is a textbook conflict of interest. That is why many attorneys treat self-translation as an avoid-if-possible option, especially for core civil status documents.

For a deeper analysis of self-translation, see Can I translate my own documents for USCIS?

2. Can a Friend or Family Member Certify a Translation?

Yes, a friend can certify a translation for USCIS if they are genuinely competent in both languages and sign a proper certification with their name and contact details.

The problem is not the legality. The problem is the risk profile.

- If your friend makes a tiny date or name mistake, it immediately raises questions about competence.

- If your friend shares your last name, impartiality becomes an issue.

- If the certification looks informal (“I promise this is correct, signed: Uncle Tom”), it stands out against the thousands of formal certificates officers see every year.

In my experience, a “free” friend translation is often the most expensive option. Your friend does not want to say no to you. They spend hours doing you a favor, and then one small error or informal phrase leads to a months-long RFE.

3. Can a Notary Certify a Translation?

This is one of the most persistent myths I see in consultations: “USCIS needs it notarized.”

A U.S. notary public’s job is to verify identity and witness signatures. Unless the notary is also the actual translator and truly competent in both languages, their stamp does not prove translation accuracy.

For USCIS filings, the key requirement is a certified translation with the correct statement of accuracy and competence. A notary seal is usually optional and, by itself, insufficient.

Some courts, consulates, or foreign agencies may ask for notarization or even an apostille on top of the certified translation, but that is a separate requirement. For USCIS alone, notarization is almost never the core issue.

We explain this in detail in Certified vs Notarized Translation.

4. Professional Certified Translation Services (Agencies)

This is the option most immigration lawyers quietly prefer: a translator or agency that specializes in immigration documents, issues formal certificates, and is familiar with USCIS expectations.

A proper USCIS-certified translation from a professional service typically includes:

- Full, literal translation of the document, including headings, seals, stamps, and back-side content.

- A separate certificate of translation accuracy for each document.

- The translator’s or company’s full name, address, and contact details.

- Professional letterhead that makes verification easy for officers.

If you want to see how a finished package looks, review our USCIS certified translation sample.

Comparison Table: Self vs Friend vs Notary vs CertOf

| Option | USCIS Acceptance Risk | Expert Verdict | Typical Cost | Time Cost | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-translation | High (conflict of interest, high scrutiny) | Avoid for USCIS filings | $0 | Several hours of your own time | Low-stakes, non-USCIS, informal understanding only |

| Friend or family | Medium to high (quality and impartiality concerns) | Risky for core civil documents | Coffee, dinner, or a favor | Several hours of their time | Minor evidence, not birth/marriage/divorce certificates |

| Notary only | High if no proper translator certification | Insufficient by itself | $15–$50 per signature | Travel + appointment time | Identity verification, not translation accuracy |

| Professional service (e.g., CertOf) | Low (designed around USCIS standards) | Recommended for immigration filings | From $9.99 per page | Minutes for standard documents | Birth, marriage, divorce, police, court and other core evidence |

For most I-130, I-485, and N-400 cases, paying the equivalent of a few cups of coffee for a professional certified translation is cheaper than risking months of delay over a free favor from a friend.

Common 2025 Pitfalls That Lead to RFEs

Here are the patterns we see again and again in real USCIS files:

- One “blanket” certificate for multiple documents: Officers may treat some documents as uncertified if it is unclear which statement applies to which translation.

- Partial or summarized translations: Skipping seals, stamps, or back-side content is treated as an incomplete translation of a foreign-language document.

- Raw machine translation: Dropping a Google Translate output into Word and signing it puts all the legal responsibility on you, with none of the professional credibility.

- No contact information for the translator: A certificate with only a first name and no way to reach the translator is more likely to be questioned.

- Chaotic layout: If the translation has no visual relationship to the original, officers must work harder to match fields. In a high-volume environment, that rarely helps your case.

We cover rejection scenarios in more detail in USCIS rejected my translation: what went wrong?

How CertOf Solves “Who Can Certify a Translation” in 3 Steps

At CertOf, we designed our process for people who want professional quality without law-firm pricing. Instead of debating who can certify a translation, you can treat it as a fast, controlled step in your filing checklist.

- Upload your documents: Visit CertOf’s online certified translation portal and upload clear scans or photos of your documents.

- Review your quote and confirm: See your instant price (starting at $9.99 per page), confirm the language pair and purpose (USCIS), and pay securely online.

- Download your USCIS-ready package: For many standard documents, you receive your certified translation in minutes as a PDF, with mirror formatting and a separate certificate for each document, ready to print and include in your USCIS packet.

Every USCIS-certified translation from CertOf includes:

- Full, literal translation of the original document.

- Document-specific certificates of translation accuracy that follow 8 CFR 103.2(b)(3).

- Company letterhead and contact details, so officers know exactly who is responsible.

- Clear digital delivery, so you can reprint the translation for future filings if needed.

Ready to move this off your to-do list? You can start here: get your USCIS-ready certified translation online.

FAQ: Who Can Certify a Translation for USCIS?

Does USCIS require translations to be notarized?

In most USCIS filings, the critical requirement is a certified translation with the proper accuracy and competence statements. A notary seal is usually not required. Some courts, consulates, or other authorities may ask for notarization on top of the certified translation, but that is a different requirement from USCIS’s own rule. See Certified vs Notarized Translation for details.

Can a friend certify a translation for USCIS?

Yes, a friend can certify a translation if they are genuinely fluent in both languages and sign a proper certification. However, because of impartiality and quality concerns, this option is much more likely to draw questions than a professional service. For key civil documents used in I-130, I-485, or N-400 filings, I generally recommend using a professional certified translation instead of relying on favors.

Can I reuse the same certified translation for multiple USCIS cases?

Often yes. If the underlying foreign-language document has not changed, a properly certified translation can usually be reused in future USCIS filings or stages. Always check whether the form instructions ask for “recent” documents, and see our guide on how long a certified translation is valid for USCIS.

Does USCIS accept online certified translations and PDFs?

Yes. In practice, USCIS regularly accepts printed copies of certified translations obtained online, as long as they include a real signature, the required certification language, and clear identification of the translator or company. You keep the original PDF and print a clean copy to include in your packet. CertOf’s workflow is designed around this pattern.

How do I know if a translator is “competent” in USCIS’s view?

USCIS does not run a central licensing exam for translators. Instead, officers look at the translation itself and the certification: Is the translation complete and consistent? Is the certification professionally written? Can the translator or company be clearly identified and contacted if needed? Using a specialized USCIS-certified translation service is the simplest way to signal competence and reduce avoidable questions.